Benjamin “Bennie” A. Haertel, Jr.

15 June 1895 – 24 July 1915

The Eastland, one of five chartered excursion boats meant to ferry employees, their families and friends from Chicago over to the Michigan City shore for the annual Western Electric Company picnic, keeled over into the Chicago River while still at dock, trapping hundreds inside its hull and leading to the deaths of 844 of the 2,500 passengers aboard at the time of the incident which became known as The Eastland Disaster.

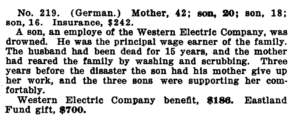

Bennie was the oldest surviving of four sons born to German immigrants Minnie (Donath) and Benjamin Haertel. Minnie was born in Brandenburg in 1872 and came to the us in mid-1892; Ben Sr came to the U.S. in 1886 at the age of 16. They married in 1892, and their first child, Arthur, was born and sadly died it seems during their first full year of marriage. (I could not find any public records but a family ancestry report put the date as 1893; it was definitely prior to 1900 per Minnie’s responses to the children born/children still living questions on the 1900 and 1910 censuses.)

Bennie was born in June 1895, Ervin in 1897; and Elmer in 1899. The family appears together in the public records only once — on the 1900 census. There they were shown living as one of three families at 891 13th Street in the West Town neighborhood. Ben Sr’s profession was listed as stove repairer. Tragically, Ben Sr would pass away just five months after that census information was recorded, less than a month prior to what would have been his 30th birthday. I did some searching to try and determine if this may have been an accident, but I didn’t find any relevant news items or family notes, so his cause of death remains the usual Illinois mystery.

The Red Cross report done 15 years later tells us the story of what happened next. With three children under six years old to care for and no obvious familial support showing up in any public records, Minnie had to go to work “washing and scrubbing.” Due to the children being at home, my best guess as to what that entailed is that she took in washing and perhaps did cleaning for others as time went on and the boys were in school or Bennie was old enough to watch his little brothers.

By 1910, Bennie was old enough to go to work and is the only one in the household with an occupation listed (helper at a factory), though he was only 14 years old. In 1909, Chicago enacted a massive street renumbering project, and though they were listed in a different ward in 1910 and at a new address, both of which imply they’d moved a very long way from their prior apartment — in reality, they appear to have only gone around the corner. According to the Red Cross report, Minnie continued to work until about 1912, so it’s likely — even though her 1910 occupation was listed as “none” and “own income” given as her industry — that she continued to do washer work and together she and Bennie were keeping the family afloat.

Around 1912, per the report, Bennie was making enough money that Minnie was able to stop her own work outside the home. By that time, Ervin would also have been old enough to go to work and it’s likely the sons wanted to take over the burden of support from their mother and did.

Bennie started working for Western Electric in early 1913 and at some point before his death, the family moved farther west and farther south in the 11th ward. It also appears they were renting a house rather than a flat in a multi-family building, but that part is unclear. The address is currently a newer business building in a neighborhood where very old and more recent, replacement buildings sit side-by-side, so you can get some sense of how it might have been in 1915.

From this new address on South Leavitt Street, Bennie was taken to Emanuel Evangelical Lutheran for his funeral and from there to Concordia to rest beside his father. There’s no indication that any of his family members had boarded the Eastland with him, and while we can’t know for sure, I imagine he had looked forward to some care-free fun with his work friends, casting off family responsibility for one day. It’s also possible he was the only one who wanted to be up in time for the first boat and the others planned to follow him later. His brothers appear to have been working elsewhere at the time, so a third possiblity is that they simply couldn’t get the day off to join Bennie.

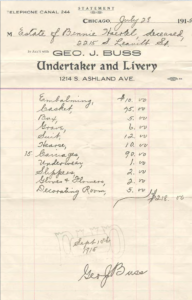

The Red Cross summarizes the family’s situation in 1915 this way: “…the three sons were supporting [their mother] comfortably” which must have been what Bennie had always hoped to accomplish. Due to Minnie being a widow, Bennie’s survivors received a fairly sizeable relief payout. Western Electric paid $186.75 for Bennie’s burial (which covered most but not all the expenses per the itemized bill), and the Eastland Fund gift totalled $700, a considerable sum for the time.

Almost three years later in June 1918, Ervin’s draft card indicated the family was still living on South Leavitt, and he was working at Western Electric. As we’ve no indication he was also working at WE when Bennie was alive, this was likely a job he started after Bennie’s death as part of WE’s push to hire relatives to help out victims’ families. In September of the same year, Elmer filled out his own draft card, indicating he was working as a clerk at the Board of Trade which I expect was a very good job for a young man.

Ervin ended up serving, but that late in the war and that close to its end, it’s unclear if he ever shipped out. He was mustered out in December of the same year. Elmer does not appear to have been called up at all, which isn’t surprising as his draft card was filled out less than two months before the Armistice.

In 1920, the family were all back together on South Leavitt, but Ervin had started working as a sign painter. Elmer was still at the Board of Trade. In 1923, Ervin married Rose Kriha Lafferty, a divorcee with two daughters. The break with her first husband appears to have been complete as her younger daughter took Ervin’s surname and neither daughter was mentioned in their bio-father’s obituary. Ervin and Rose had no children of their own. Ervin continued to work as sign painter for many years and later owned a tavern.

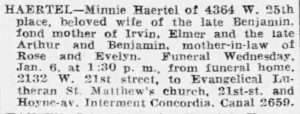

Elmer continued to work at the Board of Trade and lived with his mother through the 1930 census, according to which another move had taken place, this time to 22nd Place, still in the same general area of the city where they’d always lived. Elmer married Evelyn Freitag in 1936 and during this same period went to work for a private brokerage. Tied to this marriage, they also moved to West 25th Place, living in a two-flat (or duplex) house alongside Evelyn’s brother and his family. It is this address that is listed on Minnie’s obituary as her home, so we know youngest Elmer cared for his mother until the end. Minnie was 64 years old when she died and joined her son and husband at Concordia.

Her obituary is the kind I always hope to find in these cases — it lists not just her late husband but also Bennie and even baby Arthur alongside their brothers who lived long enough to grow old. Elmer and Rose had no children together, and Ervin’s stepdaughter who took his name never married nor had children, so this branch of the Haertel family sadly came to an end when Ervin died in February 1969, just four months after Elmer who died in November 1968.

RIP Haertels

Please visit my Instagram for any questions or comments on this post!

Thank you to the Eastland Disaster Historical Society for providing additional documentation in support of this project.